In data 24 luglio abbiamo ricevuto una mail dal Prof. Antonino Zichichi, mail inviata anche presumibilmente agli scienziati firmatari della (strana) petizione “contro le eco-bufale” (spiegata in questo post) e agli altri autori della richiesta di chiarimenti (riportata in questo post).

In data 24 luglio abbiamo ricevuto una mail dal Prof. Antonino Zichichi, mail inviata anche presumibilmente agli scienziati firmatari della (strana) petizione “contro le eco-bufale” (spiegata in questo post) e agli altri autori della richiesta di chiarimenti (riportata in questo post).

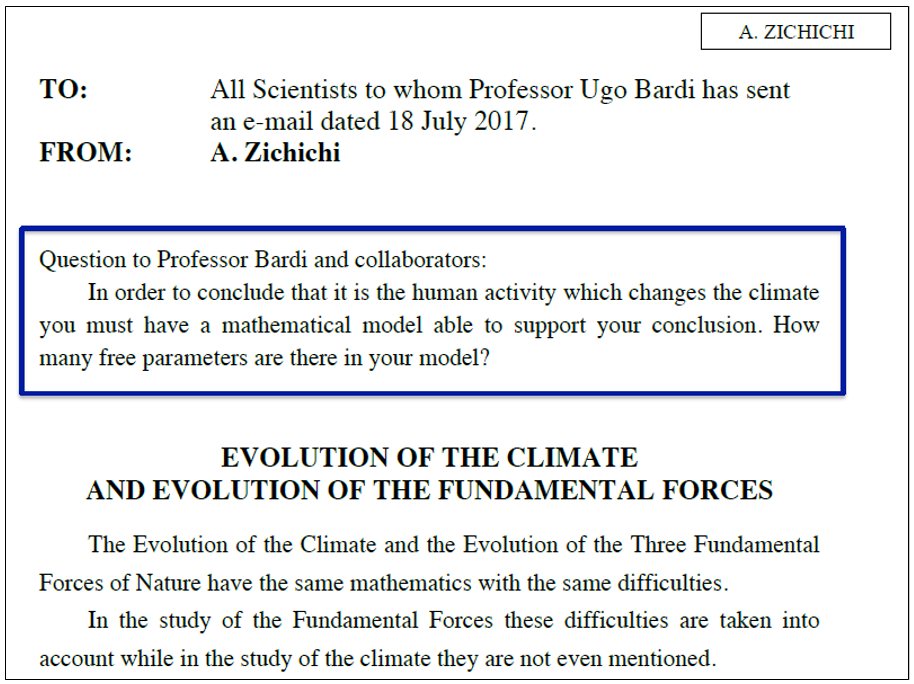

Nella mail il prof. Zichichi propone la seguente domanda ai 37 firmatari: “Per concludere che è l’attività umana che cambia il clima devi avere un modello matematico in grado di sostenere la tua conclusione. Quanti parametri liberi sono presenti nel tuo modello?”

Questa domanda è contenuta in un documento di 6 pagine di testo e 5 figure, intitolato “Evoluzione del clima ed evoluzione delle forze fondamentali” in cui il Prof. Zichichi illustra le sue ragioni (disponibile qui).

Riportiamo qui sotto la mail di risposta che abbiamo inviato al Prof. Zichichi.

Gent. Prof. Zichichi,

abbiamo ricevuto la sua mail con la domanda sul numero di parametri presenti nei modelli, questione che Lei ha già posto innumerevoli volte. Le rispondiamo sperando di aiutarla a capire questo punto, che fra l’altro non è certo tra i più complessi della scienza del clima.

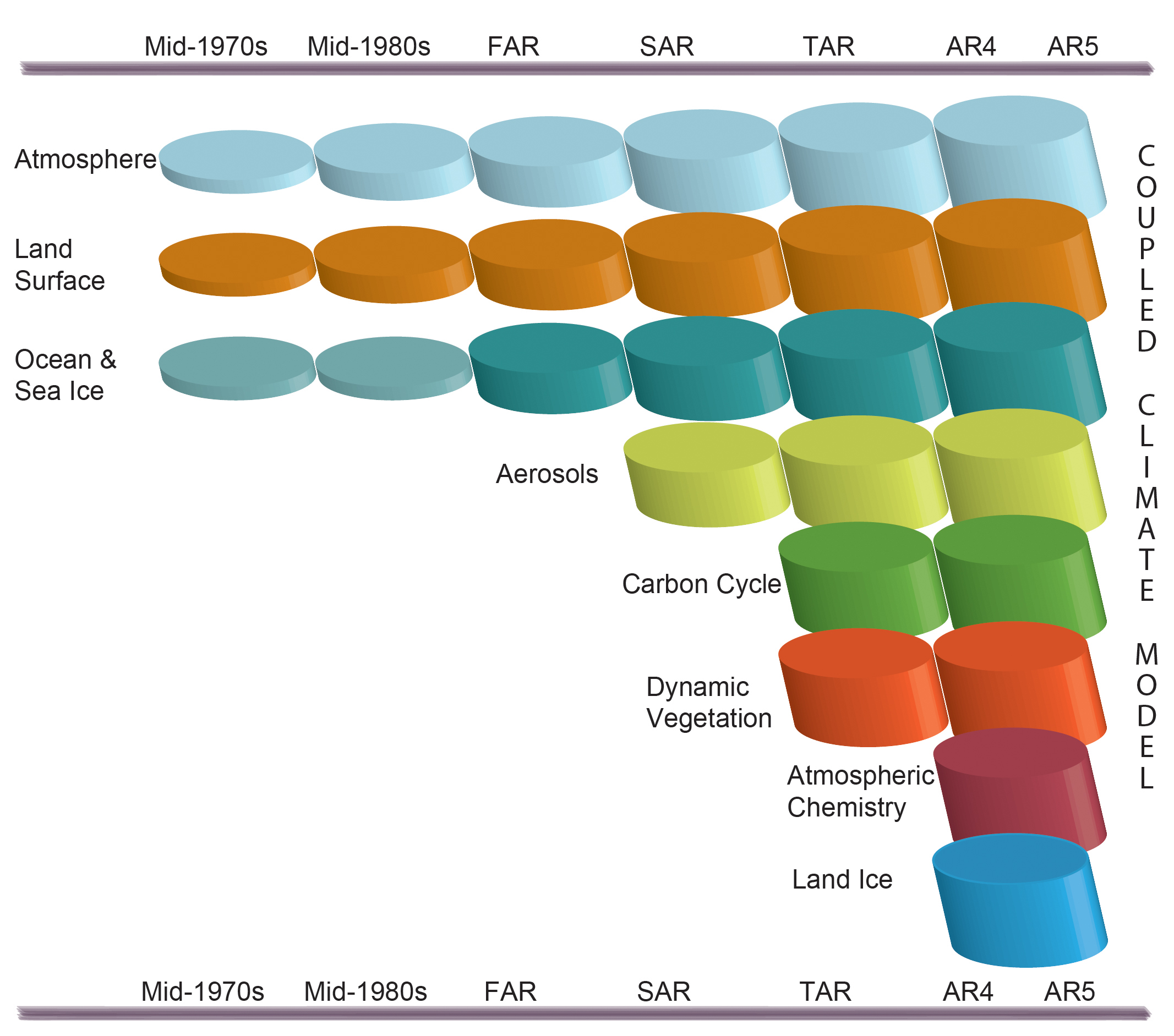

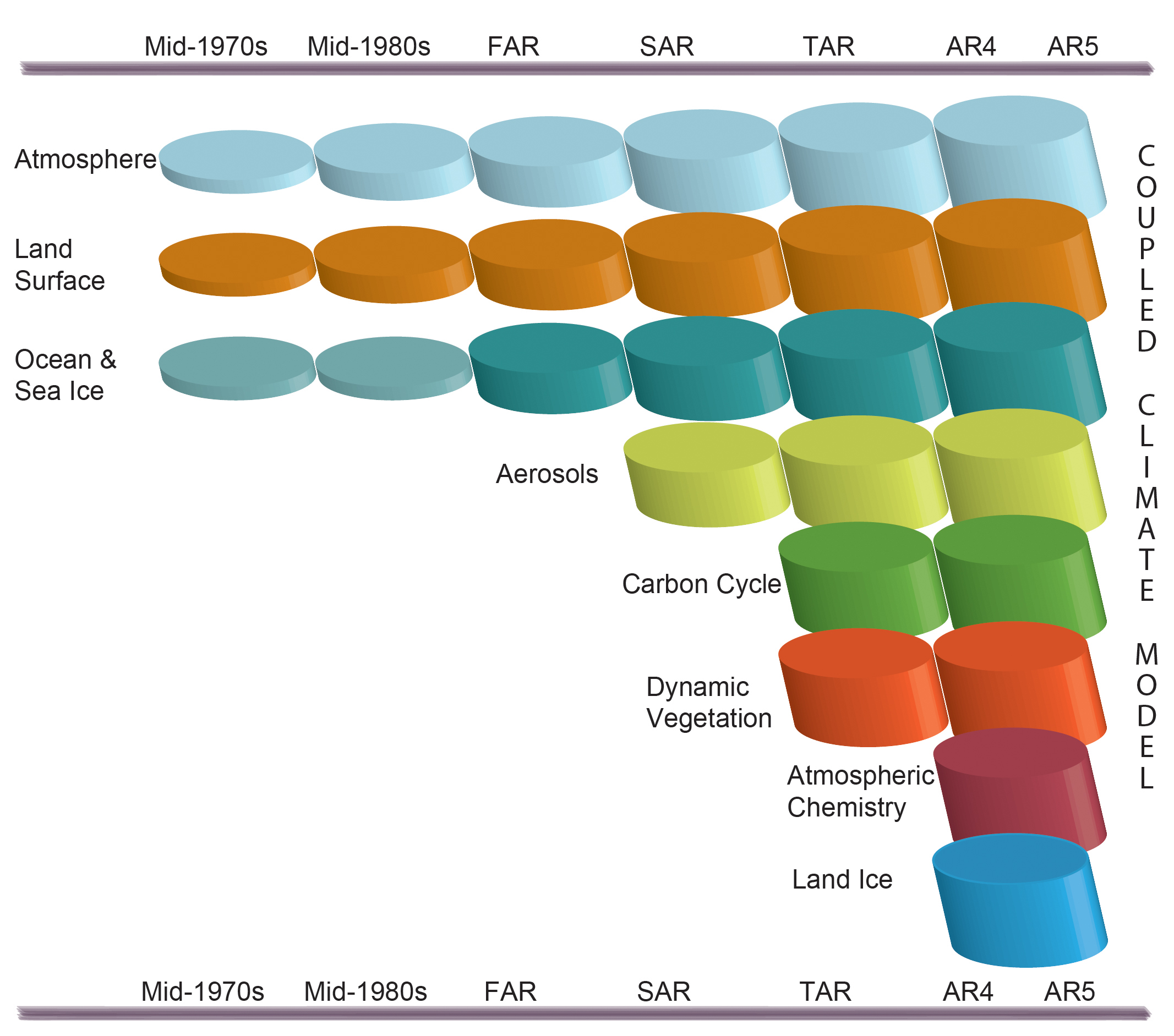

I modelli climatici hanno molti parametri, come inevitabile per modelli che descrivono un sistema complesso come è il clima del pianeta. Sono parametri di numerose equazioni diverse che insieme concorrono a definire le varie componenti del sistema climatico. La presenza di tanti parametri ed equazioni è comune a molti modelli complessi, applicati in tanti altri settori, come i modelli che governano il funzionamento degli aerei o la regolazione delle dighe. Si tratta di modelli sviluppati da almeno 4 decenni di una grande ricerca scientifica, condotta in decine di diversi centri di ricerca, da migliaia di studiosi.

I modelli sono cresciuti molto in termini di complessità (una descrizione della loro evoluzione è contenuta nel capitolo 1 del Quinto Rapporto sul Clima (AR5) dell’IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) – primo gruppo di lavoro “Working Group I Contribution to the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis”, disponibile qui, da qui è tratta la figura a fianco) e l’attività, per la taratura e valutazione dei loro risultati ha occupato una larga parte dell’attività degli scienziati.

I modelli sono cresciuti molto in termini di complessità (una descrizione della loro evoluzione è contenuta nel capitolo 1 del Quinto Rapporto sul Clima (AR5) dell’IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) – primo gruppo di lavoro “Working Group I Contribution to the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis”, disponibile qui, da qui è tratta la figura a fianco) e l’attività, per la taratura e valutazione dei loro risultati ha occupato una larga parte dell’attività degli scienziati.

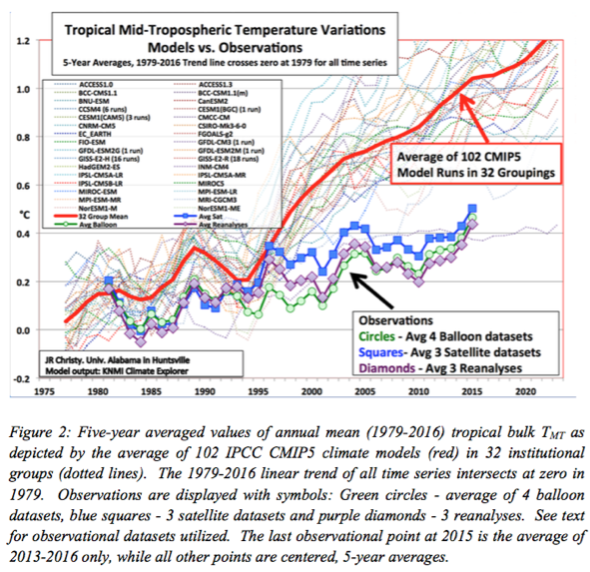

L’IPCC, che effettua una raccolta e revisione della principale letteratura scientifica peer-reviewed nei vari campi della scienza climatica, ha dedicato nell’ultimo rapporto AR5, sempre nel volume del primo gruppo di lavoro, un intero capitolo a questo tema, intitolato “Evaluation of Climate Models”: 126 fitte pagine contenente 6 tabelle e 47 figure, con circa 1150 riferimenti a pubblicazioni scientifiche, in cui vengono date risposte a molti temi complessi relativi al funzionamento dei modelli climatici.

Mentre la lettura e comprensione di queste pagine richiede competenze sulla climatologia e la modellistica dei sistemi fisici e naturali, le segnaliamo che un Box presente nel capitolo, “Box 9.1 – Climate Model Development and Tuning” (pag. 749 qui) è stato scritto con un linguaggio divulgativo per rispondere alle domande semplici come quella che Lei ha posto.

Le riportiamo qui il testo di questo Box:

“Box 9.1 | Climate Model Development and Tuning

The Atmosphere–Ocean General Circulation Models, Earth System Models and Regional Climate Models evaluated here are based on fundamental laws of nature (e.g., energy, mass and momentum conservation). The development of climate models involves several principal steps:

- Expressing the system’s physical laws in mathematical terms. This requires theoretical and observational work in deriving and simplifying mathematical expressions that best describe the system.

- Implementing these mathematical expressions on a computer. This requires developing numerical methods that allow the solution of the discretized mathematical expressions, usually implemented on some form of grid such as the latitude–longitude–height grid for atmospheric or oceanic models.

- Building and implementing conceptual models (usually referred to as parameterizations) for those processes that cannot be represented explicitly, either because of their complexity (e.g., biochemical processes in vegetation) or because the spatial and/or temporal scales on which they occur are not resolved by the discretized model equations (e.g., cloud processes and turbulence). The development of parameterizations has become very complex (e.g., Jakob, 2010) and is often achieved by developing conceptual models of the process of interest in isolation using observations and comprehensive process models. The complexity of each process representation is constrained by observations, computational resources and current knowledge (e.g., Randall et al., 2007).

The application of state-of-the-art climate models requires significant supercomputing resources. Limitations in those resources lead to additional constraints. Even when using the most powerful computers, compromises need to be made in three main areas:

- Numerical implementations allow for a choice of grid spacing and time step, usually referred to as ‘model resolution’. Higher model resolution generally leads to mathematically more accurate models (although not necessarily more reliable simulations) but also to higher computational costs. The finite resolution of climate models implies that the effects of certain processes must be represented through parameterizations (e.g., the carbon cycle or cloud and precipitation processes; see Chapters 6 and 7).

- The climate system contains many processes, the relative importance of which varies with the time scale of interest (e.g., the carbon cycle). Hence compromises to include or exclude certain processes or components in a model must be made, recognizing that an increase in complexity generally leads to an increase in computational cost (Hurrell et al., 2009).

- Owing to uncertainties in the model formulation and the initial state, any individual simulation represents only one of the possible pathways the climate system might follow. To allow some evaluation of these uncertainties, it is necessary to carry out a number of simulations either with several models or by using an ensemble of simulations with a single model, both of which increase computational cost.

Trade-offs amongst the various considerations outlined above are guided by the intended model application and lead to the several classes of models introduced in Section 9.1.2.

Individual model components (e.g., the atmosphere, the ocean, etc.) are typically first evaluated in isolation as part of the model development process. For instance, the atmospheric component can be evaluated by prescribing sea surface temperature (SST) (Gates et al., 1999) or the ocean and land components by prescribing atmospheric conditions (Barnier et al., 2006; Griffies et al., 2009). Subsequently, the various components are assembled into a comprehensive model, which then undergoes a systematic evaluation. At this stage, a small subset of model parameters remains to be adjusted so that the model adheres to large-scale observational constraints (often global averages).

This final parameter adjustment procedure is usually referred to as ‘model tuning’. Model tuning aims to match observed climate system behaviour and so is connected to judgements as to what constitutes a skilful representation of the Earth’s climate. For instance, maintaining the global mean top of the atmosphere (TOA) energy balance in a simulation of pre-industrial climate is essential to prevent the climate system from drifting to an unrealistic state. The models used in this report almost universally contain adjustments to parameters in their treatment of clouds to fulfil this important constraint of the climate system (Watanabe et al., 2010; Donner et al., 2011; Gent et al., 2011; Golaz et al., 2011; Martin et al., 2011; Hazeleger et al., 2012; Mauritsen et al., 2012; Hourdin et al., 2013).

With very few exceptions (Mauritsen et al., 2012; Hourdin et al., 2013) modelling centres do not routinely describe in detail how they tune their models. Therefore the complete list of observational constraints toward which a particular model is tuned is generally not available. However, it is clear that tuning involves trade-offs; this keeps the number of constraints that can be used small and usually focuses on global mean measures related to budgets of energy, mass and momentum. It has been shown for at least one model that the tuning process does not necessarily lead to a single, unique set of parameters for a given model, but that different combinations of parameters can yield equally plausible models (Mauritsen et al., 2012). Hence the need for model tuning may increase model uncertainty. There have been recent efforts to develop systematic parameter optimization methods, but owing to model complexity they cannot yet be applied to fully coupled climate models (Neelin et al., 2010).

Model tuning directly influences the evaluation of climate models, as the quantities that are tuned cannot be used in model evaluation. Quantities closely related to those tuned will provide only weak tests of model performance. Nonetheless, by focusing on those quantities not generally involved in model tuning while discounting metrics clearly related to it, it is possible to gain insight into model performance. Model quality is tested most rigorously through the concurrent use of many model quantities, evaluation techniques, and performance metrics that together cover a wide range of emergent (or un-tuned) model behaviour. The requirement for model tuning raises the question of whether climate models are reliable for future climate projections. Models are not tuned to match a particular future; they are tuned to reproduce a small subset of global mean observationally based constraints. What emerges is that the models that plausibly reproduce the past, universally display significant warming under increasing greenhouse gas concentrations, consistent with our physical understanding.”

Speriamo che questo testo le possa essere d’aiuto per trovare la risposta alla sua domanda; le suggeriamo comunque di leggere l’intero capitolo per ulteriori dettagli.

Riguardo al testo che ci ha inviato, dobbiamo ammettere di averlo trovato davvero poco comprensibile e poco congruente con la domanda da Lei stesso posta. Nella parte iniziale abbiamo infatti rilevato diverse affermazioni senza fondamento ed errori basilari di comprensione della scienza del clima (ad esempio quella secondo cui le difficoltà nello studio del clima non sarebbero mai menzionate), errori che del resto hanno caratterizzato la quasi totalità dei suoi scritti sul tema del cambiamento climatico che abbiamo potuto leggere negli ultimi 15 anni.

La invitiamo quindi ad approfondire un minimo la scienza del clima, prima di esprimersi sui mezzi di comunicazione.

Infine, la invitiamo ad essere più rispettoso del lavoro dei molti studiosi, anche italiani, che con passione e serietà lavorano per migliorare giorno dopo giorno gli strumenti più adeguati che oggi abbiamo a disposizione per capire l’evoluzione dell’interferenza umana con il clima del pianeta.

Distinti saluti

Ugo Bardi, Università di Firenze

Daniele Bocchiola, Politecnico di Milano

Stefano Caserini, Politecnico Milano

Claudio Cassardo, Università di Torino

Sergio Castellari, Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia

Claudio Della Volpe, Università di Trento

Gabriele Messori, Stockholms Universitet

Elisa Palazzi, Istituto di Scienze dell’Atmosfera e del Clima (ISAC-CNR)

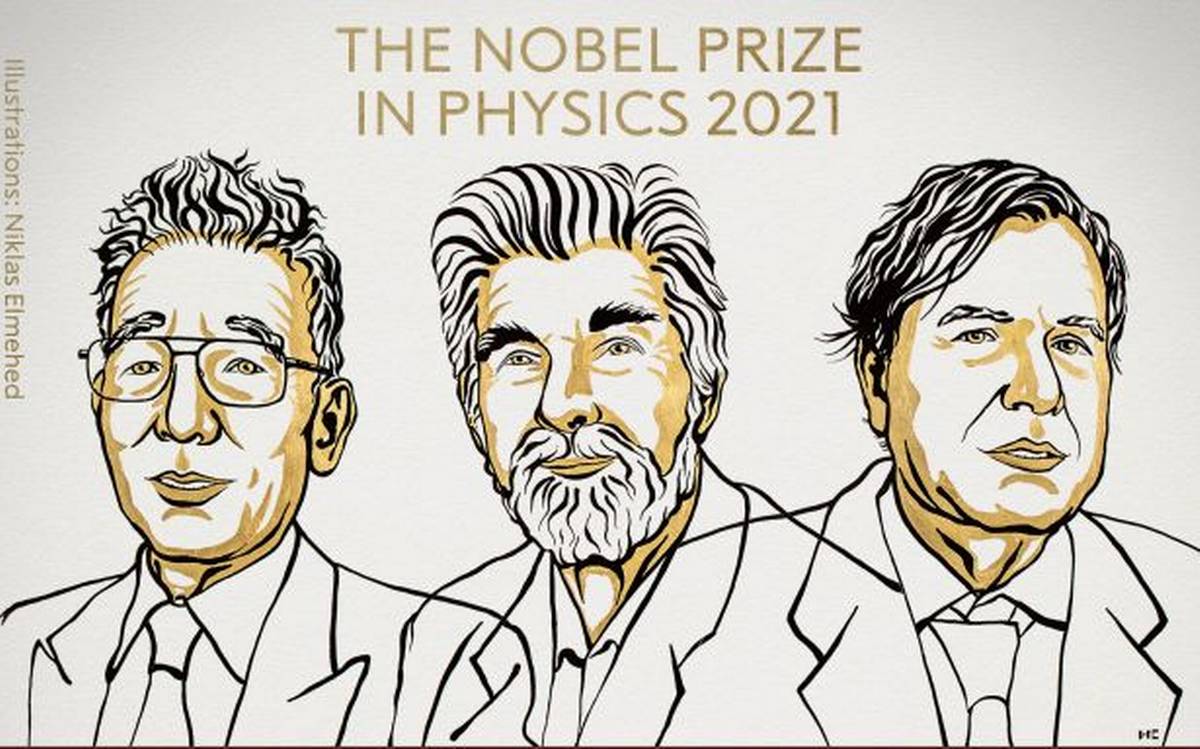

Secondo John Wettlaufer della Yale University, la reazione di Syukuro Manabe alla notizia dell’essersi laureato Premio Nobel in fisica per il 2021 è stata di assoluta sorpresa, sottolineata dal commento: “But I’m just a climatologist! (Ma sono solo un climatologo!)”.

Secondo John Wettlaufer della Yale University, la reazione di Syukuro Manabe alla notizia dell’essersi laureato Premio Nobel in fisica per il 2021 è stata di assoluta sorpresa, sottolineata dal commento: “But I’m just a climatologist! (Ma sono solo un climatologo!)”.

In data 24 luglio abbiamo ricevuto una mail dal Prof. Antonino Zichichi, mail inviata anche presumibilmente agli scienziati firmatari della (strana) petizione “contro le eco-bufale” (

In data 24 luglio abbiamo ricevuto una mail dal Prof. Antonino Zichichi, mail inviata anche presumibilmente agli scienziati firmatari della (strana) petizione “contro le eco-bufale” ( I modelli sono cresciuti molto in termini di complessità (una descrizione della loro evoluzione è contenuta nel capitolo 1 del

I modelli sono cresciuti molto in termini di complessità (una descrizione della loro evoluzione è contenuta nel capitolo 1 del

L’osservazione delle variazioni climatiche del passato recente e in corso e la stima di quelle future costituiscono il presupposto indispensabile alla valutazione degli impatti e alla definizione delle strategie e dei piani di adattamento ai cambiamenti climatici. Se la conoscenza delle variazioni del clima passato e presente si fonda sulle osservazioni e sull’applicazioni di metodi e modelli statistici di riconoscimento e stima dei trend, quella del clima futuro si basa essenzialmente sulle proiezioni dei modelli climatici.

L’osservazione delle variazioni climatiche del passato recente e in corso e la stima di quelle future costituiscono il presupposto indispensabile alla valutazione degli impatti e alla definizione delle strategie e dei piani di adattamento ai cambiamenti climatici. Se la conoscenza delle variazioni del clima passato e presente si fonda sulle osservazioni e sull’applicazioni di metodi e modelli statistici di riconoscimento e stima dei trend, quella del clima futuro si basa essenzialmente sulle proiezioni dei modelli climatici. Nonostante la grande distanza e le differenza climatiche e topografiche, una potenziale evoluzione comune unisce Europa ed Asia, ed il cambiamento climatico potrebbe giocare un ruolo fondamentale.

Nonostante la grande distanza e le differenza climatiche e topografiche, una potenziale evoluzione comune unisce Europa ed Asia, ed il cambiamento climatico potrebbe giocare un ruolo fondamentale. Nel precedente post

Nel precedente post In un lavoro pubblicato sulla rivista Journal of Climate

In un lavoro pubblicato sulla rivista Journal of Climate Il prossimo 22 maggio si svolgerà a Seoul, presso la

Il prossimo 22 maggio si svolgerà a Seoul, presso la  I negazionisti dei cambiamenti climatici non trovano più argomenti nuovi, che siano in difficoltà?

I negazionisti dei cambiamenti climatici non trovano più argomenti nuovi, che siano in difficoltà? Chissà se esiste uno scienziato del clima laureato in scienze del clima. Lei in che cosa si è laureato?

Chissà se esiste uno scienziato del clima laureato in scienze del clima. Lei in che cosa si è laureato?